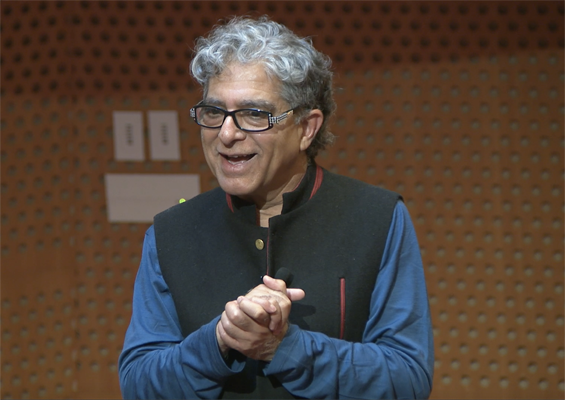

It can be hard to find time for self-reflection and consideration of one’s role in the greater world, especially this time in the semester. Luckily, attendees of Deepak Chopra’s xTalk on Dec. 3 were given time to do just that, in the midst of a far-reaching talk on the trustworthiness of reality and the relationship between bodies and consciousness. The renowned lecturer, philosopher, physician and best-selling author launched into his presentation with a simple question — “What is reality?” — and in just about forty minutes, teased out a few giant universe-upturning questions that fuel his own philosophical pursuits and notion of what it means to be human.

The question of how humans define reality is a key reference point and guiding provocation for Chopra’s thoughts on the relationship between mind and biology. Where, in space, does our mind, our thoughts, our consciousness, exist? What is the biological source, the physical origin point, of thought? Consciousness can’t be studied like other sciences, argues Chopra, because it has no form — no unit of measure, no clear concept to even be measured. All we have, he proposes, is stories, crafted from what our limited perception provides.

This is in part due to our language — when we name something, we identify it as a discrete thing that can then be studied. That thing becomes the premise for another thing, and before you know it, there are entire structures that rest upon our perception of reality, but always mediated through our senses, which are unique and in no way an unassailable interpreter of reality. A butterfly’s biology determines the way it sees, which is markedly different from how our biology renders vision. Is the way the human brain sees the world a truer representation of it than the butterfly’s? To Chopra, this rhetorical question extends to the body, the brain, the mind, and (inevitably) the entire universe. They are concepts we have invented to make sense of our lives, but they are, in effect, aspects of a virtual reality, no more “real” than the butterfly’s version of reality. They exist only to validate the form of consciousness we already use, by creating the vocabulary for the stories we tell to perpetuate our own existence.

Lest this all sound so destabilizing as to promote any nihilism, Chopra is convinced that science is still the best narrative humans have for making sense out of our virtual reality. We just need to remember that it’s still a story.