Step by Step Learning didn’t let the pandemic stand in the way of putting on an engaging and informative conference*. In the service of SBSL’s mission to help schools deliver evidence-based teaching and learning, the event focused primarily on pK-3 literacy.

In fact, SBSL went one better, turning the conference into a fund-raiser to support first responders and front-line workers in this time of pandemic. All told, SBSL, participants and sponsors, the latter including Acadience Learning, McGraw-HIll, PBS, ReadWa, Vosaic, and Waterford, raised $100,000 inspired by the "Go in Your Purse for a Nurse" model.

The conference spanned three days, with a star-studded roster of presenters featuring:

DAY 1: Emily Hanford, Timothy Shanahan, Joan Sedita, Freddy Hiebert, Lucy Hart Paulson

DAY 2: David Steiner, Howie Knoff, Nancy Mather, David Boulton, Jan Hasbrouck

DAY 3: Marilyn Jager-Adams, Anita Archer, Kevin Colleary, Nadine Gaab, Amanda VanDerHeyden, Laura Buccanfuso

A series of MITili blog posts over the coming days excerpts insights gleaned from select sessions across the three days (post 2 is here, post 3 is here, post 4 is here). The series begins with a session led by the incomparable Emily Hanford, senior producer and correspondent with American Pubic Media.

“What’s all the fuss about the ‘Science of Reading’?”

The so-called reading wars have raged since at least the 1960s. The point of Straight Talk was not to re-wage these wars, but rather, to offer promising paths forward. Perhaps more than anyone in the last decade, Hanford deserves credit for shining broad light on these paths.

Her reporting sums up nicely in three “documentaries”--written pieces accompanied by “podcast” tracks--released late summer each of the last three years.

- Hard to Read: How American schools fail kids with dyslexia

- Hard Words: Why aren't our kids being taught to read?

- At a Loss for Words: How a flawed idea is teaching millions of kids to be poor readers

The words that Hanford conveys from teachers--that they aren’t being adequately prepared to teach reading--pale in comparison to the heartbreaking utterings from struggling children--threatening self-harm. Tackling the first offers the best hope of eliminating the latter.

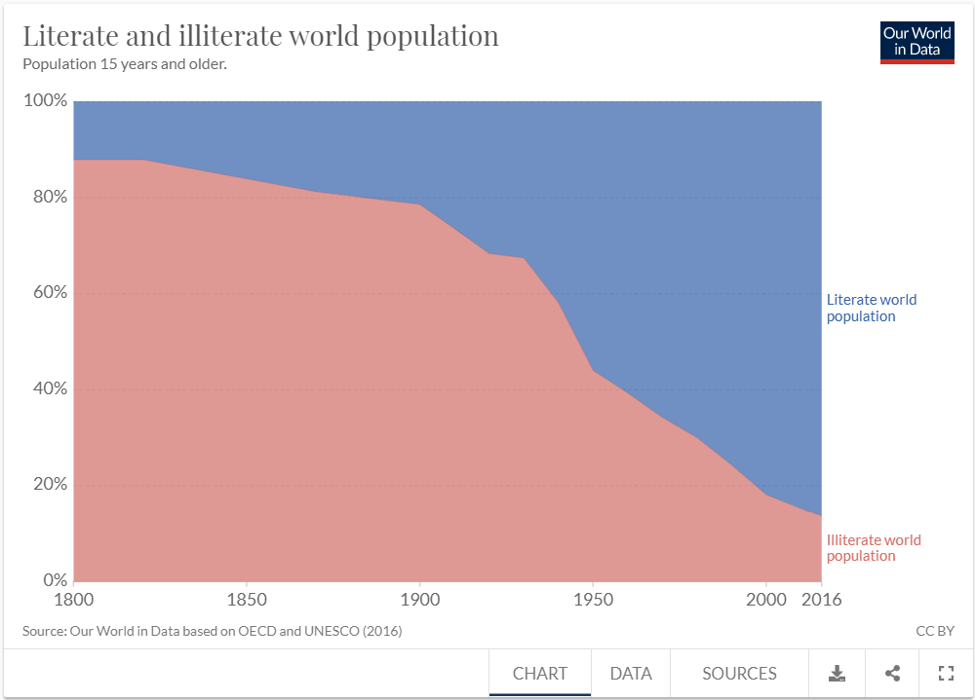

The fundamental challenge--the brain has not evolved to read or write. Process speech? Yes. Generate speech? Yes. But read and write? No. Humans simply haven’t been at it long enough.

Hanford alluded to global literacy versus time. Analysis from Roser and Oritz-Ospina shows global literacy not crossing the 50% mark until the mid-1940s.

Counter-intuitively, if it were harder for children to learn to read, we might find the problem solved. As it is, on the order of a third of all children learn to read almost regardless of the form of instruction. A form of selection bias results--if some children learn to read, then the instruction must be sound. And the fault therefore must lie within the children who struggle.

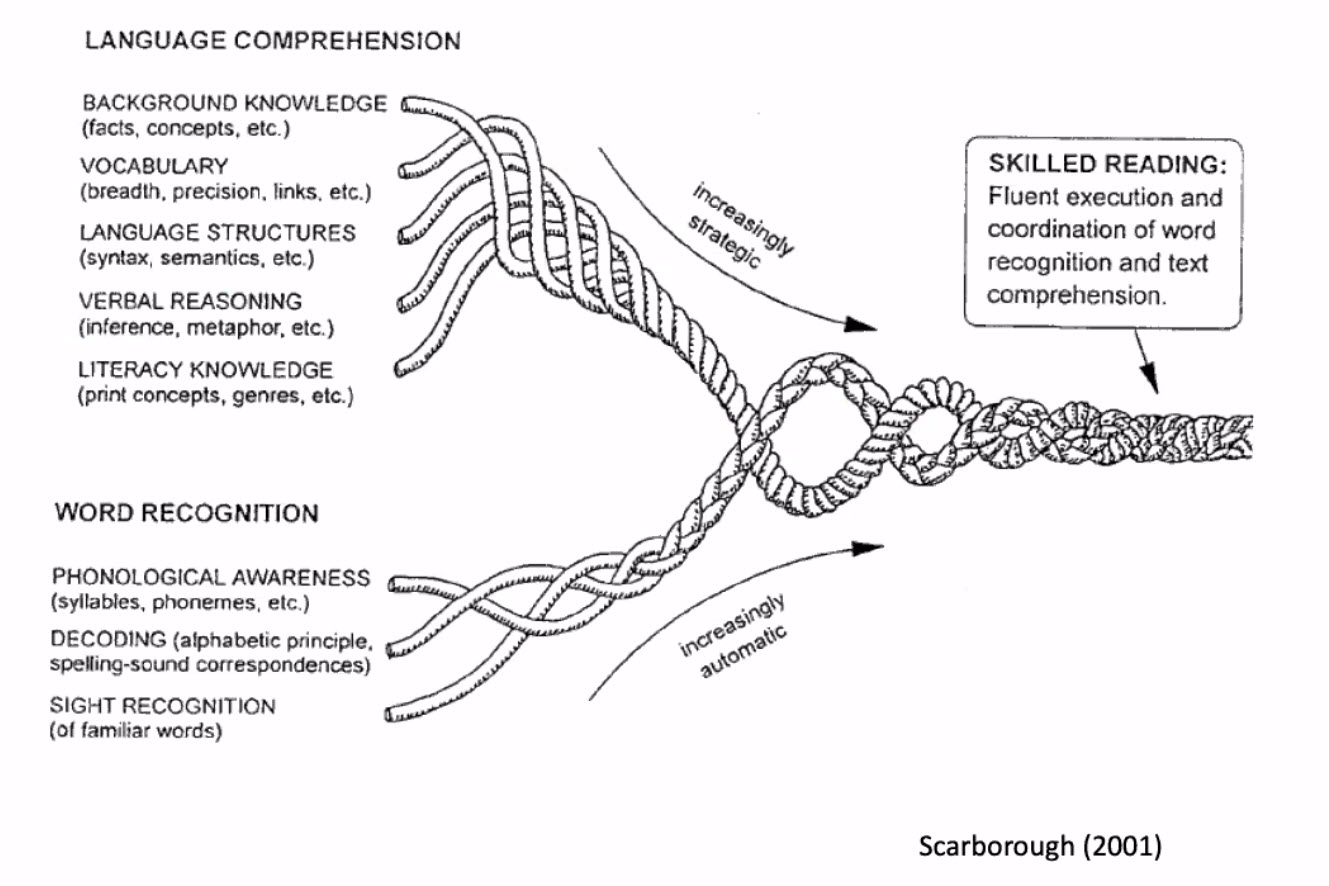

Hanford reminded participants of Gough and Tunmer’s 1986 “Simple View of Reading” that lies at the heart of what’s sometimes called “direct instruction:” namely, that reading comprehension is the product of decoding (the phonics ability to match speech sounds to letters) and (spoken) language comprehension. Either without the other, and the reader struggles.

Too many reading programs pay mere lip service to phonics. The programs begrudgingly include phonics as an optional afterthought, more for marketing than instructional purposes. At the core of many of these programs: an approach called “three-cueing” that occupies the “whole language” ground opposite direct instruction.

Children learn to rely on (1) graphic cues (“what do the letters tell you about what the word might be?”), (2) syntactic cues (“what kind of word could it be, for example, a noun or a verb?”), and (3) semantic cues (“what word would make sense here, based on the context?”).

What’s wrong with three-cueing? Compared to sound reading, it’s far too slow and occupies valuable brain cycles that should instead be focusing on comprehension. Research shows that skilled readers don’t use three-cueing … but poor readers do.

Skilled readers, on the other hand, know tens of thousands of words on sight, learned via repetition in a process called “orthographic mapping.” The automaticity that orthographic mapping provides frees the brain to focus on the true objective--comprehending rich text.

The science of reading shows the direct instruction way. So why hasn’t the evidence-based approach swept the nation, instead finding itself impeded by “balanced literacy,” which at its base is simply whole language dressed up in contemporary clothing?

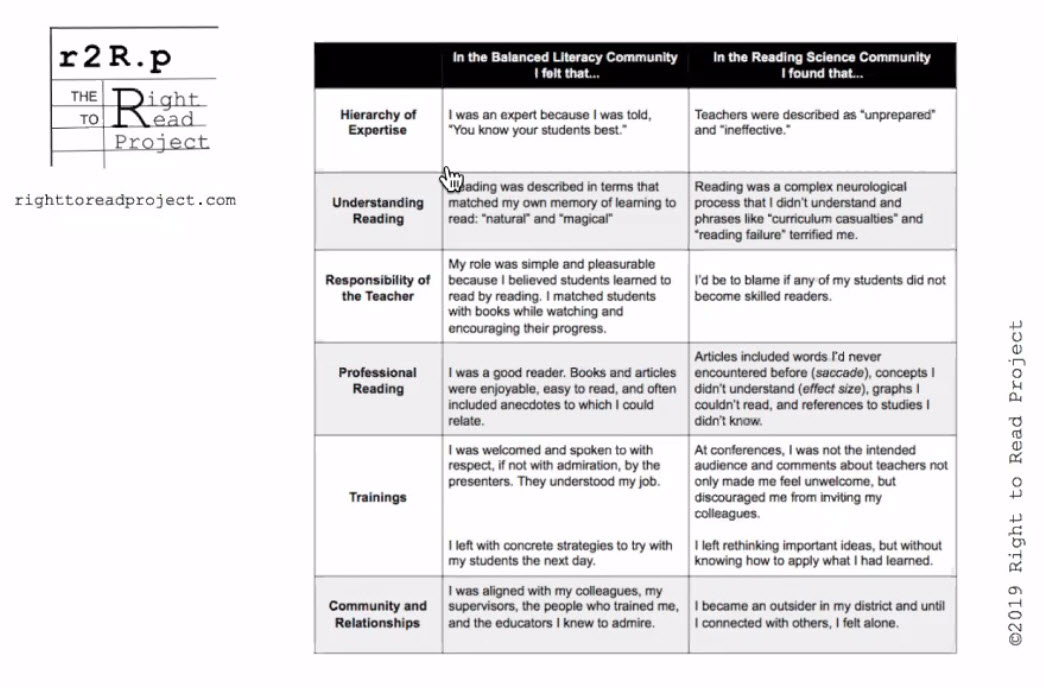

Hanford shares a rarely encountered insight. Whether by luck or design, balanced literacy welcomes teachers. Images of storytime and children immersed in books connote a warmth in sharp contrast with the cold white lab coats of science. Balanced literacy feels easy. And feels right.

Academic papers, R-squared, and confidence intervals emanating in an unfamiliar language from university laboratories feels off-putting. And even if they were to get the language and tone right, the researchers aren’t continually there to support teachers the way the balanced literacy community does.

Hanford concluded with a compelling graphic from The Right to Read Project how teachers feel in the balanced literacy community versus that of reading science.

The Right to Read Project graphic hints at promising paths forward that reading science researchers should support.

- At the pre-service and in-service levels, help prepare teachers, don’t describe them as unprepared

- Use inviting, “natural” images such as Scarborough’s “Reading Rope” from 2001 (below), to intuitively and visually tie together underlying concepts

- Help teachers see the gains their students are making

- Save academic speak for the academy--engage teachers with “plain English”

- Advocate for and enable ongoing coaching at the school level

- Equip teachers following the evidence base with approaches to enlist their colleagues